Metropolitan Police Service officer and NPAA Coordinator Jess Rick talks about her diagnosis with ADHD, and the challenges and strengths it brings

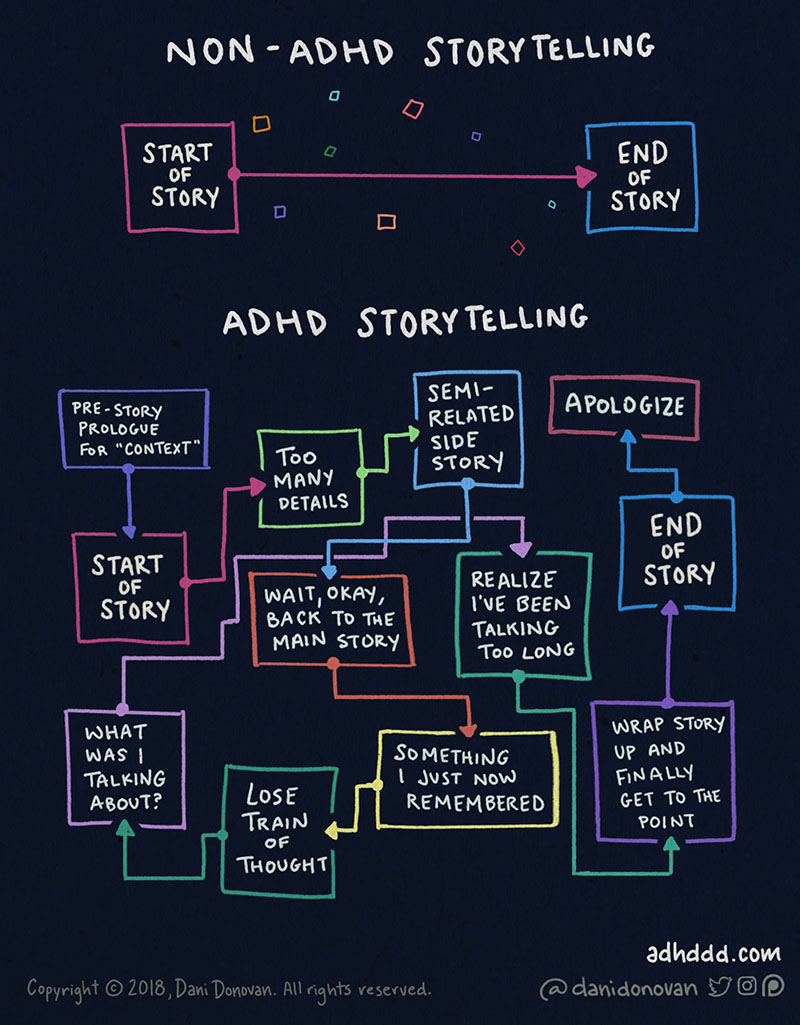

Never ask someone with ADHD to tell you a story, because this is what happens:

But here we go, I will try anyway.

I have been asked to write this blog as October is ADHD Awareness Month. ADHD is Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Someone once described it as “ADHD is not a deficit of attention; in fact it is an abundance of attention. The challenge is controlling it!”

ADHD may conjure up stereotypes of ‘naughty boys’ or children who can’t sit still. And by and large, that is true – after all, stereotypes come from somewhere, right? However, although four times more boys than girls are diagnosed with ADHD in childhood, by adulthood the ratio of males with ADHD to females with ADHD is more like 1:1.

I was one of those girls who didn’t appear in the statistics for children with ADHD, but I would appear in the adult statistics. Officially, I have only had ADHD since February 2020. But in reality, I’ve had it for 32 years because it is a lifelong condition. There are times where the ADHD is more obvious and times where it is less obvious, but it hasn’t gone away – it’s still there, and the chances are that if the signs are harder to spot then the person with ADHD is making some considerable effort to hide these signs.

So why is there such a gulf between these figures? Why are so many more males than females diagnosed in childhood, and vice versa? Mainly, this is due to the fact that symptoms in boys are generally more obvious and external: constantly running around, not being able to sit still, acting impulsively and in some cases being physically aggressive. Girls are more likely to internalise their symptoms and be withdrawn, anxious and daydreamers with low self-esteem.

For women who are not diagnosed in childhood, their ADHD generally only becomes apparent in later life when they try (and fail) to juggle work, family and other responsibilities. And when they try to seek help or understanding, they are very often misdiagnosed with other conditions such as anxiety, depression and in some cases personality disorders.

Whether male or female, everybody who has ADHD will have some (or all) of these signs and symptoms:

- Short attention span, especially for non-preferred tasks

- Hyperactivity, which may be physical, verbal, and/or emotional

- Impulsivity, which may manifest as recklessness

- Fidgeting or restlessness

- Disorganization and difficulty prioritising tasks

- Poor time management and ‘time blindness’

- Frequent mood swings and emotional dysregulation

- Forgetfulness and poor working memory

- Trouble multitasking and executive dysfunction

- Inability to control anger or frustration

- Trouble completing tasks and frequent procrastination

- Distractibility

For me, my ADHD started to become apparent when I was 17 and in sixth form. I was described by my teachers as someone who was ‘intelligent, but needed to apply herself a little more to achieve her full potential’. Without too much effort I achieved 10 GCSEs, all B grades or higher, but in sixth form it all unravelled and I barely scraped a pass in 2 A-Levels, only achieving C, D and E grades. My head of sixth form stated I would never get in to university and therefore would never amount to anything.

Luckily I had no intention of attending university and instead joined the Met, initially as a PCSO and then as a PC. However I began to struggle when I was on response team and my ADHD became even more apparent as I couldn’t understand why, having had a previously successful stint on response, I was struggling so badly now. My self-esteem got worse, and I developed anxiety and depression and found myself trapped in a cycle where the harder I tried, the more I kept struggling. It was like drowning – the more I kicked to try and keep my head above water, the further I sank. Eventually, I was given a choice: leave response, or be subject to the performance management process. I chose the former.

It would take me another four years before I was diagnosed with ADHD. Only now can I begin to understand who I truly am. I’m not an idiot, I’m not a failure. My brain is wired differently, and while I am disorganised and lose focus very easily, I am disciplined enough to (along with the help of my medication) control my distractibility to a certain extent. I am learning to stop setting myself ridiculously high and unachievable standards which knock my self-esteem when I don’t achieve them.

Most people perceive ADHD as something negative. But for me it makes me who I am. And it’s not always negative. I work very well under pressure – if I have to get something done by a certain deadline, I will pull out all the stops to get it done, and get it done to a high standard. I am extremely resilient – I guess I’ve had to be with all the hurdles I have had to overcome! If I’m struggling with managing my time or knowing which task to prioritise over others, instead of using neurotypical techniques to try and help (and then being surprised when they don’t work because I am not neurotypical!) I find some ADHD-friendly techniques instead.

My life may have ended up differently to what I originally imagined, but I wouldn’t swap having ADHD for anything.

I will finish with a quote I have stolen from a colleague in the MOD Police who also has ADHD as he says it much better (and with fewer words) than I can. He says: “Don’t be harsh on yourself. Stop viewing the world from a neurotypical vantage point that sees your traits as negatives, and understand that you are different and special. You have unique gifts, and to steal a quote from a colleague, each of us is simply a different kind of clever. So – forget your weaknesses and seek out your strengths.” ∎