In this personal account, Ministry of Defence Police Sergeant Dan Harris reflects on his ADHD diagnosis and how his understanding of the condition allowed him to recognise his strengths and achievements

I first started writing this blog based around my experience of ADHD in January 2021. The original draft contained gems of information encased in multiple layers of drivel that would likely reduce the reader to abandonment after a few lines. I felt the article needed to relay my journey in terms of pre- and post-diagnosis and how it impacted on my life during both phases due to the traits. On reading it through, it felt like a monotonous trudge along a barren motorway.

I once spoke to a fellow police service ADHD-er – what struck me about this individual was their extraordinary positivity regarding their condition. In my mind, I remember thinking that we were looking at the condition from two completely different perspectives; and for the briefest of moments, through this dialogue I was able to experience how they completely accepted and embraced each aspect of ADHD lovingly and with no judgement. I momentarily wore their perspective like an item of clothing, hoping it would fit. This was a garment they had spent significant time lovingly weaving, but regrettably I just couldn’t get it to stay in place; it felt wrong and it didn’t conform. I concluded that my colleague’s life experiences had been significantly kinder than mine.

My personal journey into ADHD did not commence until 2018. I am now 45 years of age so its fair to say I have spent a significant portion of my life not knowing I had this condition. Sadly, this is not unusual as ADHD is only really observed (usually by others) when it explodes in what can only be described as uncontrollable behaviour, which more commonly manifests in young male children. It’s a sorry situation when a condition is only treated or noticed when it becomes intolerable, but sadly this lack of understanding is not just confined to ADHD – it’s endemic in most neurodivergent conditions.

Media coverage has most likely perpetuated the stereotyping that exists around ADHD, and if this is the fire then some professionals who are perhaps ill-informed and really ought to know better must surely be the fuel. A significant problem here is that most stereotyped ADHD behaviour appears typical in young males, and since some can mask this behaviour as they grow older, it perpetuates the damaging perception that ADHD is a childhood condition. There are also other negative connotations: many females are either are not as aggressive with the condition – and thus more malleable – or they struggle with the attention deficit element which is again less obvious to spot. But of even more significance is not all males with the condition can be expected to conform to the stereotypical norm either, and their chances of being diagnosed are even more significantly reduced, as is evidenced by both my son and I.

My own diagnosis came about after my son was diagnosed as there were similarities between us. However, my son excelled during his initial schooling and then seemingly fell into a precipice when he had to take responsibility for his own learning on conclusion of secondary education. Sadly, by comparison I struggled with the early part of schooling and whilst I was respectful and well-behaved, I never really achieved much in the initial schooling years. During my personal exploration pre-diagnosis there were elements of ADHD that seemed to resonate with me and an online screening test via the informative Additude website seemed to strongly suggest I might have the condition. At around this time I had informed my line manager of my desire to seek diagnosis and he responded by stating “Why do you want to go and get yourself a label?” I clearly remember the time of day, the room we were stood in and the wave of anger that I managed to stifle as I explained why this was so important to me.

Whilst I was finishing off my first draft of this blog, the above incident was one of many I can recount since diagnosis, and I reflected on childhood more than I have ever done before. I could seldom remember a positive word written by teachers in my school reports, and perhaps even sadder is that my parents cared even less because they had zero expectations of me and had effectively written me off at a young age through comparisons with my three older siblings. Until I started writing this piece, I held great resentment towards them post-diagnosis. However, I had an epiphany that now deeply resonates: I had become everything they believed me to be, and this became deeply ingrained. Comments on my old school reports may strike a chord with some of you; in my day I theorised that teachers must have held rubber stamps to be wielded on those pupils who were somewhat beyond their teaching abilities. I knew they used to talk in the staff room, and I believed they must have shared the same labels and used them every year on my reports. My stamps were: “needs to pay attention”, “easily distracted by others”, “has proven on occasions that he is able, but is simply not trying hard enough”, “nice lad tries hard”, and so on. One teacher once got so frustrated when I expressed concerns over an inability to grasp his teaching that he informed me I would amount to nothing, becoming a person subjected to the ‘mushroom theory’. To my delight he then embellished this further, informing me that I would be locked in a dark room my entire life and fed on excrement (he of course used the somewhat more common word!) This was the first and only time that I learned something in one of his lessons.

I cannot thank the NPAA enough for allowing me to write this blog, as it led to something quite profound happening. When reflecting on my past I began recounting all the self-perceived negative traits of my condition, and then linked them to moments where I had failed in one way or another. I had forgotten about school reports, lack of belief from parents and most (but not all) teachers. I thought about profound moments of failure and directly linked them to my condition – I had done this since diagnosis with more recent failures, so going back further wasn’t too difficult. The defining moment however came in an extremely rare moment of stillness: in my mind, I pondered on why I needed to perceive my condition so negatively. At first, I thought it could be down to my turbulent experience since diagnosis and my battle to have my condition accepted. But in the end, the real reason needed that moment of stillness in order to cut through negative self-perception.

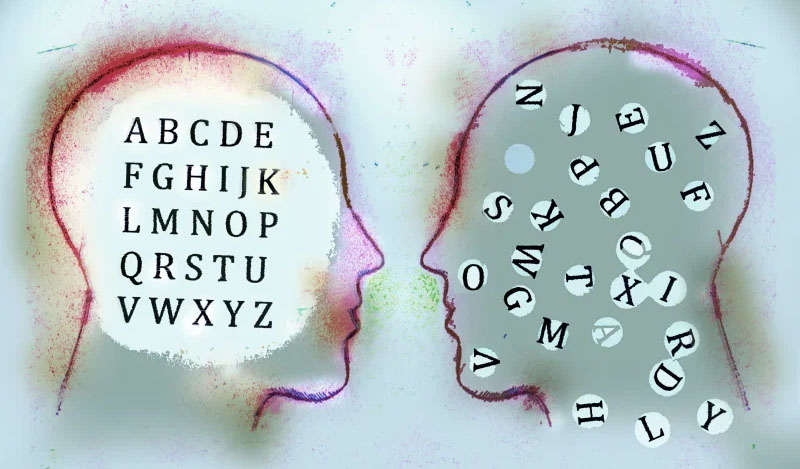

After diagnosis I searched for signs of all the negative traits synonymous with ADHD, and with every passing day I discovered something new, leaving little point in looking too far back in my life. The condition is held in such poor esteem, and some will question its existence even in the face of overwhelming evidence. If you are new to ADHD, can you immediately identify any positive traits of the condition as you read this blog? The poor perceptions and stereotypical views were the perspective that I was judging myself from, and it was from this basis that I was searching for evidence to justify my diagnosis to others. The problem being the more I did it, the more people normalised some of my traits which I made me feel like they were being dismissive and simply added further frustration.

It’s impossible to ignore the negative elements of my condition, especially in challenging environments where there is very little support, but I now know I can now choose how I allow these moments to affect me. I can continue championing the condition whilst educating others, and I can now stop searching for those negative traits and celebrate the positive ones. During my attempts to justify the existence of my condition, others were keen to highlight minor successes as if they were some huge significant achievement, but the reality was these were relatively ordinary in comparison to my neurotypical peers. Colleagues with similar intelligence had easily negotiated these hurdles and beyond, and many had left me behind in my 22 year career including student officers I had trained. My perception was that these minor achievements were being highlighted to qualify my colleagues’ rationale for not needing to support me. Far worse though were the feelings that they were effectively suggesting I had achieved so much for a person with ADHD.

My perception of self has now changed thanks to this blog, and I no longer view it from that old perspective. Writing this piece caused a period of reflection where I suddenly diverted from my old destination in favour of a much shorter and more interesting route. I now know that very few of my neurotypical peers would have been able to overcome the mental barriers I overcame over the years, even if my achievements in doing so were mundane compared to what they achieved. Few will have picked themselves up from continual rejection and displayed an almost superhuman forms of resilience. Better still, I also realised I had a unique set of gifts afforded to me that were gathering dust due to my former misdirected focus. I am learning to weave a garment from my own unique brand of ADHD which fits me perfectly, and if a person can’t accept who I am that says more about them than me.

I will now present my former perspective of my ADHD and follow with a more positive perspective – but first, a common quote which resonates with me: “If you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing it is stupid”. This is credited to Albert Einstein, whom many have suspected was ADHD.

- There are times in my life where I have been left frustrated by my carelessness and this has resulted in failing in some aspirations when competing with other people. ADHD has gifted me with high levels of resilience and taught me how to bounce back from rejection and failure.

- I can be terribly messy and leave things lying around. My ADHD creates a phenomenon where items cease to exist until I am reminded of them, and then searching for them can be frustrating and take time. As a coping mechanism I place things in line of site where they are never forgotten – I also habitually place them in the same location, although this can seem messy to others. (See Einstein’s desk for example.) Whilst this niggles my neurotypical colleagues, this simple process highlights my highly adaptable abilities as my differently wired brain finds ways to adapt to its neurotypical foreign environment. I am the fish out of water.

- My disorganisation can lead to tasks being missed. I have a superpower of hyperfocus which provides me with boundless energy to keep going until a task is complete and within the deadline. I do sometimes miss deadlines, and I occasionally miss non-critical deadlines in an unsupported environment. However, when there is an urgent task you can rely on my extreme energy levels and hyperfocus to kick and see the task through to completion with seconds to spare.

- I can’t prioritise and can only manage one small task at a time. I now realise this was a mis-sold perception that I invested far too much time and belief in. I can in fact multi-task – see above for those critical deadlines! ADHD folk benefit from breaking down tasks into short sprints affording each with a ‘win’ at the end. I had previously been trying to apply neurotypical techniques, and it was this approach that created disastrous results.

- I hardly sleep compared to others. Some nights I just can’t stop my brain from its constant internal dialogue, and no matter how hard I try I just don’t seem to get a quality night’s sleep. During these times when others are deep in the land of nod, my brain seeks solutions to problems and it is at these times I have worked through some major issues. Whilst I sleep less, I actually feel no worse for it – in fact on the rare occasions when I am able to sleep, I find my brain is less alert.

- I am easily distracted and miss things all the time. How can I possibly take a positive from that? Well it turns out that the attention deficit element of my condition is not a lack of attention, but is actually related to too much attention. ADHD folk lack the chemical dopamine which is the feel-good chemical that motivates neurotypical people to complete tasks. My brain is constantly scanning for things to stimulate the brain. This ability was also essential in prehistoric times as my people were able to constantly scan for dangers. ADHD folk were the pathfinders back in the day. My peripheral vision is constantly scanning, so it comes into its own when driving.

Other positives of my own brand which I know many others share are an unbounding energy and enthusiasm, extreme levels of resilience, and an ability to think outside the box. In fact rather than thinking outside the box I just remove the boxes completely, which can be overwhelming to some of my neurotypical colleagues!

Moving forward, I will learn ways to use my gifts to my advantage: I will recognise that the external environment is structured to cater for the majority and that by making subtle adjustments I can adapt to most environments. For those where I can’t and where there is no support enabling me to thrive, I simply need to remove myself from that location and find a place where my skills will be valued and embraced. I am currently studying a master’s degree in human resource management – I had previously attempted study pre-diagnosis and suffered a spectacular crash, but this time I have appropriate support to help me overcome my disadvantages. If there is one thing I have learnt in the first twelve months its that the human resource is a valuable commodity. When we consider policing, it can be considered the main cog in the machine, and our success depends on it. Failure to maximise the potential of everyone who is a component of that machine could ultimately result in inefficiency, but worse in my eyes is that it overlooks the opportunity to achieve maximum performance and to create a happy and inclusive working environment.

If you are embarking on the same journey of discovery for ADHD or any other neurodivergent condition, my advice is this: don’t be harsh on yourself. Stop viewing the world from a neurotypical vantage point that sees your traits as negatives, and understand that you are different and special. You have unique gifts, and to steal a quote from a colleague, each of us is simply a different kind of clever. So – forget your weaknesses and seek out your strengths. ∎