Ministry of Defence Police Inspector Dan Harris argues that a ‘one size fits all’ approach to training is preventing officers with neurodivergent conditions such as autism and ADHD from entering firearms and other specialised roles

Can neurodivergent (ND) conditions ever be compatible with firearms or other specialist policing roles, such as those requiring advanced driving skills?

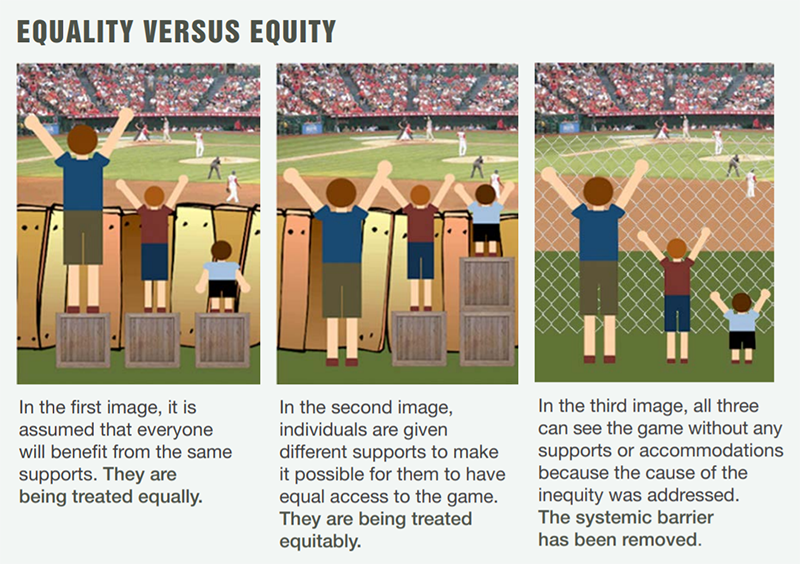

For those with lived experience or with connections to ND, there would likely be a resounding Yes: you might think that each person should be judged and supported based on their individual merits, but how can this ever be applied fairly when a ‘one size fits all’ approach is unknowingly applied by many organisations to the selection in specialist policing roles? In this blog I will dissect current approaches and present a credible argument as to why certain processes need to be abandoned to level the playing fields within specialist roles and allow those of us who think and present differently to be given an equitable chance to fulfil our career aspirations. After all, why should someone who thinks in a different way be excluded any more than someone who has an overt difference such as their ethnicity or sexual orientation? To exclude the latter or allow practices that create disadvantage would rightly provoke mass disapproval, so why is it being allowed to happen to ND officers?

Whether you like it or not, if you were to present yourself to a firearms training team and disclose you are ADHD or autistic during selection, there would be immediate preconceptions drawn regarding your ability to successfully pass the necessary assessments, and likely prejudgements made regarding some of the perceived common symptoms affiliated to these conditions. At best you might have a situation where the instructors were indifferent and knew very little about your difference, but this might not make things any easier for you. If you think this can’t happen, you are wrong: I successfully negotiated assessments for the Marine Unit and Operational Firearms Commander role, only to have my authorisation cancelled because of my ADHD diagnosis.

So is there a problem, and if so where does it lie? I will present here some personal views and I welcome dialogue around these areas.

I work for a policing organisation where 98% of officers are armed. We are the largest armed policing organisation in the UK, and I can categorically state that as an organisation we are failing to address this issue appropriately, from my own experience and as noted by the NPCC and the College of Policing. There is a disparity across the UK amongst all policing organisations as to how stringent selection is for officers to pursue careers in firearms. Some organisations have a steady stream of volunteers seeking this career choice, and this not only creates competition but also generates an elitist attitude amongst those who represent the department. None of this bodes well if you are reporting being ND, and I suspect many attempting this training would avoid disclosing their difference for fear of it diminishing their chances of success.

I have conducted significant research into why policing organisations are struggling to give appropriate support to officers seeking specialist policing roles. The NPCC and College of Policing have previously highlighted the medical model of disability in their studies (more on this below), but I feel they have only merely skimmed over this topic and have failed to identify why it plays a significant part in creating disadvantage to ND officers when in direct competition with others for so few posts. Little has been done as yet to make wholesale changes which would likely generate a positive cultural shift.

It’s well-known that persons who wish to pursue firearms careers will be subjected to several assessments which include medicals and fitness tests. If successful, these officers will then be subjected to training and subsequent firearms assessments to determine suitability. In those forces where selection processes are competitive, only the best will succeed. This is where many ND applicants will fall by the wayside. Firearms training is notoriously challenging and requires full focus and attention as well as the ability to rapidly make calculated judgements. None of this is beyond those of us who present with ND difference, but I would suggest these factors can conspire against us and create challenges that others don’t have to endure.

Most forces continue to follow the medical model of disability – this is perhaps more an unconscious awareness, but few look at the ramifications of doing so when considering ND in isolation. Controversially, there will be differences in opinion even amongst our community, and research in my own organisation has exposed this. A proportion of us (I include myself in this) will not be comfortable with the label of ‘disabled’, and in my organisation, many respondents to my research reported an aversion to this label whilst still expressing experiencing difficulties in their working environments. Think about your own organisations and how ND is viewed: for most this will be treated fundamentally under disability processes, and thus the only way to evoke any kind of support is by identifying as disabled, which ordinarily requires diagnosis. Enter the medical model of disability, which seeks to label a condition and then to cure all the elements that are perceived to be negative: where a condition cannot be cured, then the person is ‘disabled’ and labelled in a manner which suggests inadequacy. I would argue that this negativity permeates into selection processes, as disability is viewed by some as being incompatible with the elite role of firearms or the high levels of driving skills needed for some specialist roles. The medical model presents perfect environmental conditions for unconscious bias to influence selection processes; for those who brave them without disclosing their conditions, the very least they can expect is extreme challenges in overcoming their differences.

“As a neurodivergent officer, I need better training, not easier assessments”

The social model of disability was first penned during the mid-nineties and was driven by an online movement, predominantly from the autistic community .This group of like-minded people vehemently refused to accept the label of disability, and the concept of ND was born. The problem was that most organisations still followed the medical model of disability, meaning that if you wanted support for a ND condition, engaging in this process was realistically the only way you could get it.

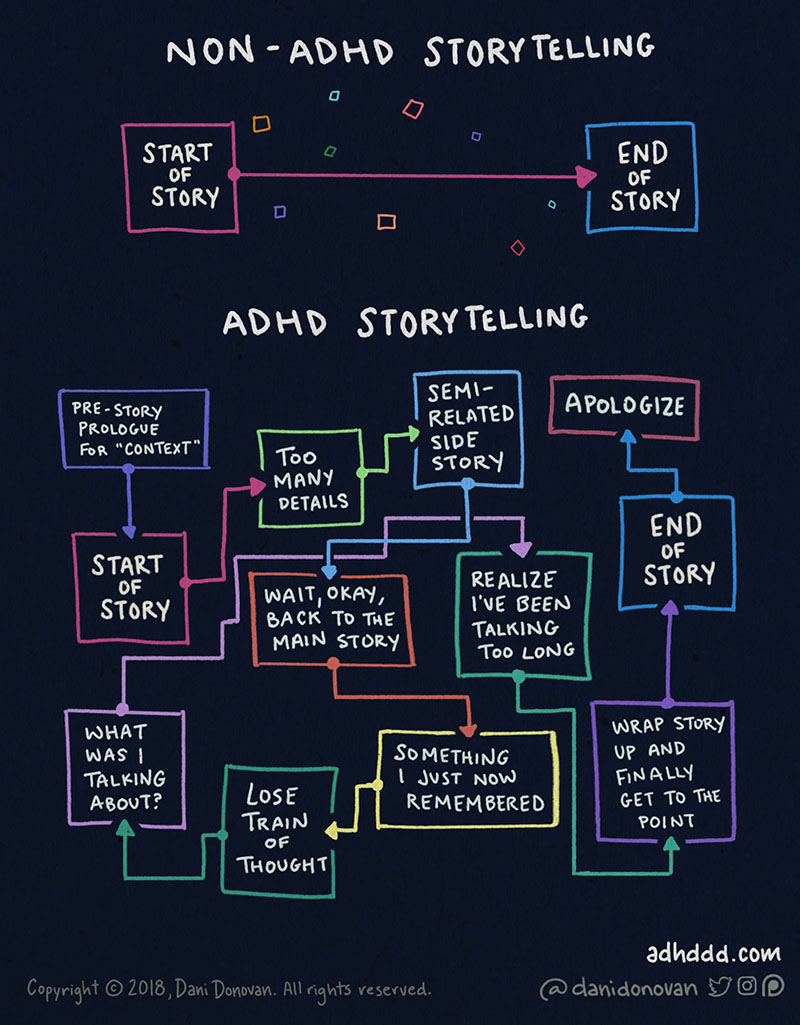

Most specialist roles including firearms and higher levels of driving will require training and then a subsequent assessment, but this is where things go wrong for those who present as ND. The training is often tailored to meet the needs of the majority and it is designed to be delivered in a limited time. Many organisations will see this time pressure as the ultimate tool in weeding out those who cannot reach the required standards. Firearms and driving instructors will argue that assessments should not be adjusted, but what might surprise them is that most ND candidates would agree. The problem does not lie in the assessments themselves, but in the teaching leading up to the assessments. More thought is needed by qualified trainers as to how training can be adapted to meet the needs of individual learners, which is a fundamental part of adult pedagogy and a skill most trainers need to possess. The other issue however is the mistrust that is generated through the medical model of disability, which will lead to some fearing disclosure of their difference. Then of course there are our colleagues who may be unaware they are ND: for the record I would argue these persons are predominantly from underrepresented groups. As psychologist Dr Nancy Doyle pointed out, having a diagnosis for a ND difference these days is a privilege that not all are fortunate to attain. Universal adjustments can address this issue, but that’s a separate discussion. The medical model not only harbours potential unconscious bias, but it also generates fear and mistrust amongst those with ND conditions.

Policing organisations need to move away from the medical model of disability, and I would agree with Dr Doyle that the social model in isolation is not the answer either. This approach suggests those who have ND should be encouraged to live with the difference rather than seeking medication or a label to highlight their difference, but this fails to consider how environments can sometimes be difficult for the individual to adapt to. This is where specialist courses have the maximum negative effect on ND people, as the teaching and time constraints challenge those of us within the ND world. We are never prepared for the subsequent assessments in the same way neurotypical people are.

Dr Doyle presents an alternative concept known as the biopsychosocial model, which encourages focus on several environmental elements when structuring policies and processes. ND should not be shoehorned under the auspice of disability once diagnosed; however, elements of the medical model need to be accepted for diagnosis. Support needs to be catered around the individual and not the perceived condition or its effects, as universally applied via the medical model. The biopsychosocial model acknowledges the uses of the medical approach to diagnose a difference, but calls for organisations to treat ND individuals according to their individual needs. The organisational needs should be balanced against the individuals in consideration of the social model approach, and when considering policies and processes I would predicate that recognising the uniqueness and incompatibility of ND within the medical model approach would be a great help towards making cultural shifts within our organisations.

When considering the Public Sector Equality duty, policing organisations need to understand that over 15% of the adult population will be ND, and the medical model of disability which underpins most organisational approaches will create inequitable practices when applying it to ND. If we want to encourage ND officers to pursue specialist policing careers and to successfully negotiate the relevant assessments, then greater care and attention is needed to support the individual according to their needs. As ND officer, I need better training, not easier assessments. ∎